18th Century

18th Century

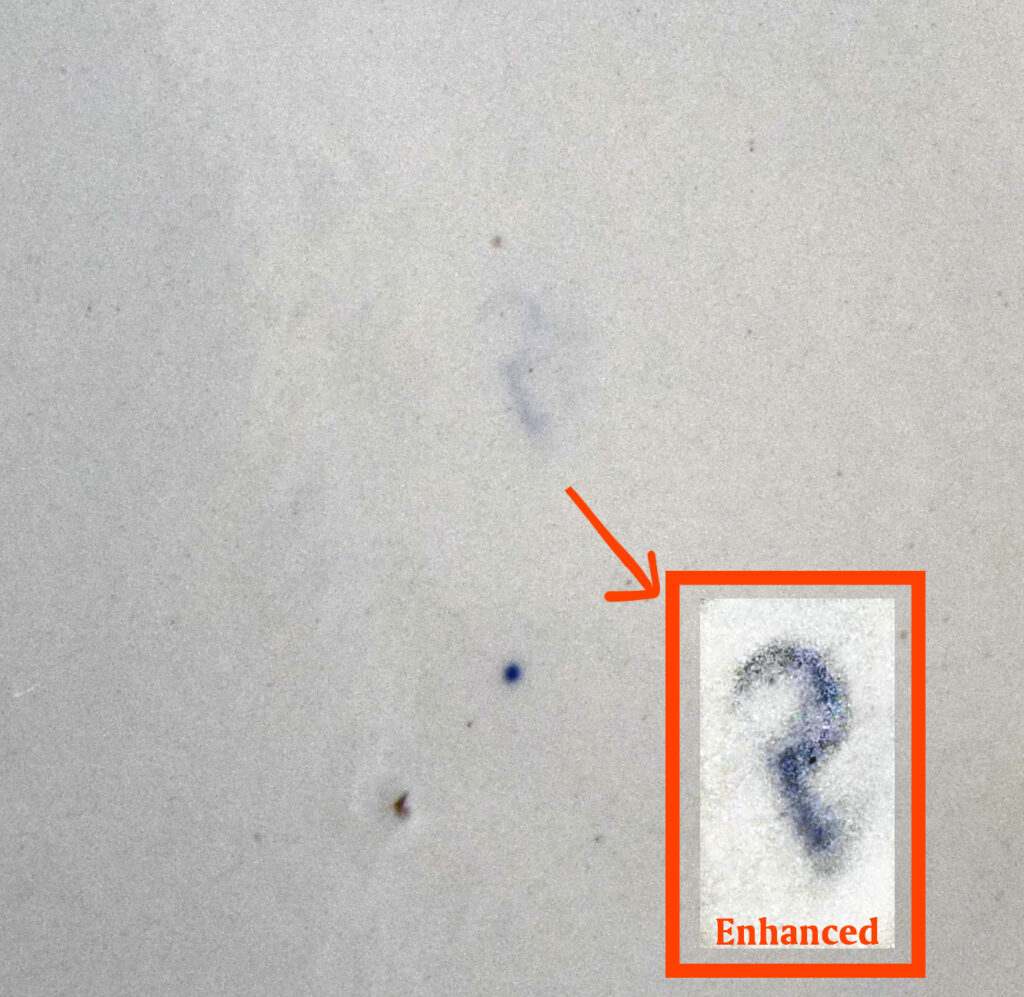

Cambrian Pottery Wales

A Question mark or astrological symbol, with the pattern, shows this to be the Welsh Cambrian Pottery (1764 – 1811). This is not the only mark of this type used by the pottery – will post more later

![<a title="By No machine-readable author provided. N@ldo assumed (based on copyright claims). [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons" href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AImariA.JPG"><img width="256" alt="ImariA" src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/ImariA.JPG"/></a>](https://marksonchina.com/marks/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ImariA.jpg)