18th Century

18th Century

Eearly Dresden and Meissen

NB: Later Meissen Marks (20th Century on) are usually printed on Transfer Printed Wares

18th Century

18th Century

NB: Later Meissen Marks (20th Century on) are usually printed on Transfer Printed Wares

17th Century

17th Century

When the Ming dynasty fell in the late 17th Century, the Dutch East India Company needed to find alternative sources for importing Porcelain in bulk to meet the increasing demand in the West. Japanese porcelain, shipped from the port of Imari, was cheap bright and colourful – in contrast to the plain blue and white from China – Imari’s most noticeable export was blue and white underglaze, embellished with gold and iron red decoration. The port name, Imari, is now synonymous with this type of decoration (some Arita ware looks similar but does not include the underglaze blue). Below, this good example of 18th Century Japanese Imari is typically distinguished by the dullness of the gold embellishment, the deep dark Indigo Blue that borders on black (frequently applied with a thick brush) and the dull orangey-red thickly (and, again, often crudely applied) surface glazed colouring under the gold.

![<a title="By No machine-readable author provided. N@ldo assumed (based on copyright claims). [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons" href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AImariA.JPG"><img width="256" alt="ImariA" src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/ImariA.JPG"/></a>](https://marksonchina.com/marks/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ImariA.jpg)

Most early Chinese Imari style patterns tended to anonymous flowers, pots and random “anonymous” patterns – typically ‘Chinese Imari’ is distinctive for its delicacy – the porcelain is thin and fine – almost brittle.

This small chinese teabowl and saucer dates from around 1740.

Like the Japanese designs, the bulk of patterns tend to focus on flowers, leaves and abstract patterns. The bright colours aged well and a hundred years later, the burgeoning English Porcelain manufacturers used the bright bold flower and abstract patterns, that typify Imari ware, in their own products. English Imari ware has been produced continuously, since it was first introduced – some patterns have also stayed, broadly the same for nearly 200 years.

For comparison – below is a photo of the wall at Badaling, showing the key features on the plate.

Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas / , via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas / , via Wikimedia Commons 16th Century

16th Century

The two rules to remember are

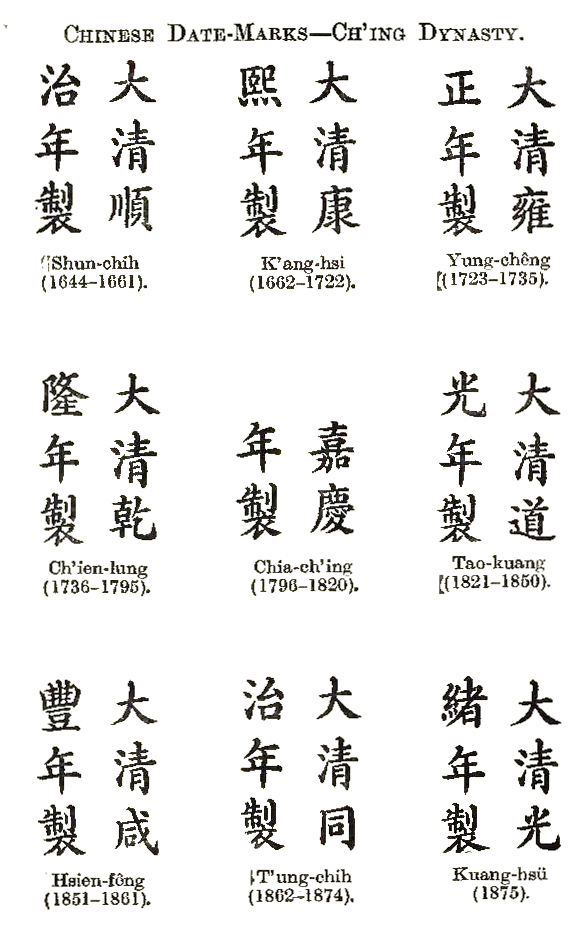

1) Having a mark on the bottom, like the reign marks in the picture for this article, does not mean that it really dates from that period.

2) Having no mark at all does not mean that it is valueless, just that the piece did not need to be stamped to sell – so was probably not intended for export.

So what does the reign mark on Chinese porcelain mean?

Yes it can mean that the piece is of the period. As you get more familiar with handling pieces (which you can do in antique fairs and shops – where they will be dated for you) you will find that there are other indicators, texture, technique, composition, colour and style that help to date each piece.

In most instances where you see a reign mark outside a museum though, it is because Chinese potters and the porcelain Studios adopted the styles of earlier generations and, if they felt the piece passed muster, would honour the memory of past masters by dedicating their piece to that period. It wasn’t originally done with the intent to defraud (tho’ it is now). It was done to say that the pot, vase, bowl, teaset was an homage to earlier artisans and the creator was proud to stand his work next to pieces of that period. A ‘don’t go old, go bold’ gauntlet to traditionalists. So many marks indicating a period before 1722 will be “apocryphal”.

Halfway through the reign of the Emperor K’ang Hsi (various spellings) he declared an abhorance of the idea that anything not intended for his and palace use should bear his mark. So it was banned with serious life threatening punishments for any infringement. Only royal porcelain was permitted to use the mark. So, after he died, everyone did it – therefore most marked K’ang Hsi pieces aren’t from the period unless they date from the beginning of his reign. Yung Cheng pieces tend to be genuine and although the post 1795 period was prolific in using older marks (including Ch’ien Lung to appeal to Western Markets), anything carrying a post 1795 reign mark is generally what it says it is – ‘Made in China’ pieces are post 1891 – and Republic – post revolution.